This game takes place in a galaxy, a very large one. Many stars, nebulae, and planets. Now, this galaxy isn’t exactly the main focus of the game, but the setting is here, if you zoom in far enough. Get close enough to one of the arms, and you’ll find a sun-like star, a bit brighter, but otherwise very similar. The game does not take place here, although it is nearby (or far, depending on the scale). So, if you look away from the star, you’ll see a few things. There’s a few planets. Go over to the fourth one.

This is the planet Kakhitt, although right now it’s unnamed. I just like to call it Kakhitt, and I probably will continue, until a species rises to sentience on this planet, and names it. Then I guess the name changes. It’s a plentiful world underwater, with nutrients almost everywhere you can see. There’s not much on land, but it’s waiting to be exploited! Although, there’s no one around to exploit, not too much. Except for one organism, that, with the proper evolution, could rise to the top. Of course, it isn’t doing much right now, just feeding off anything, really.

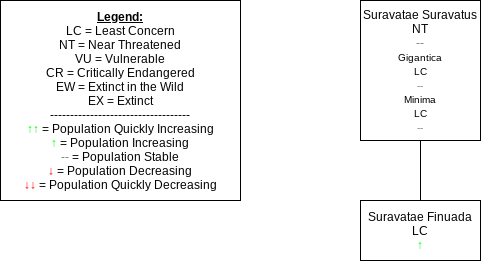

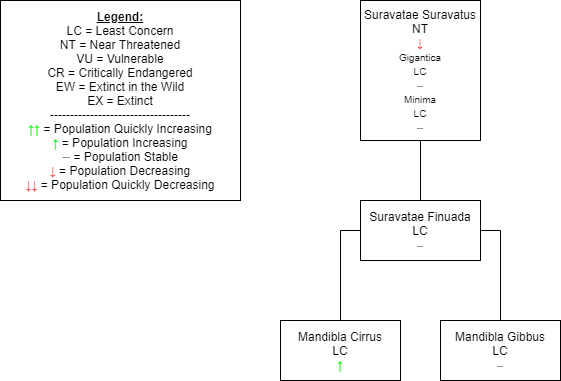

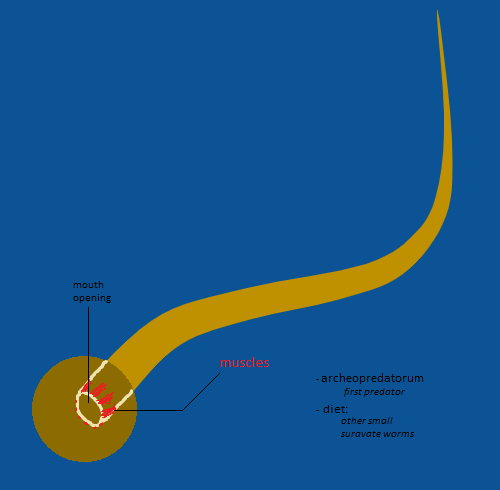

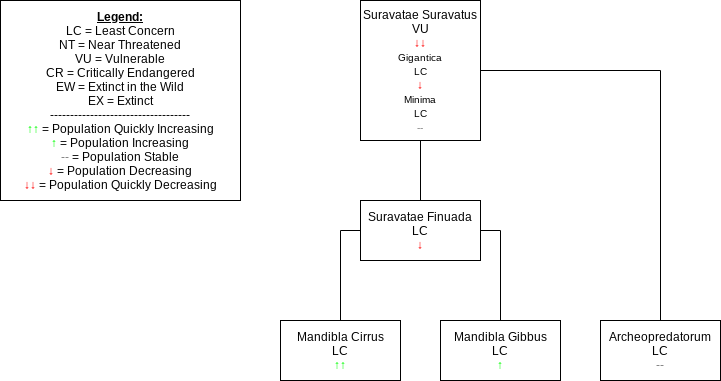

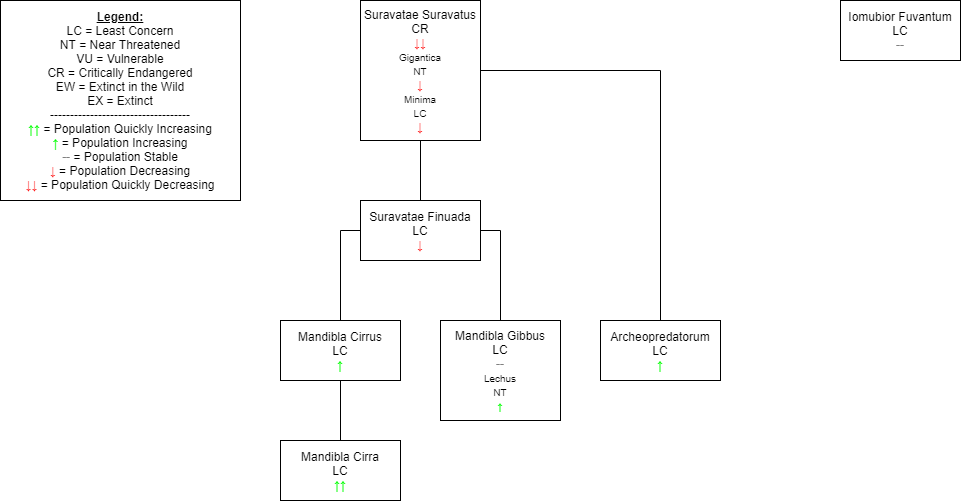

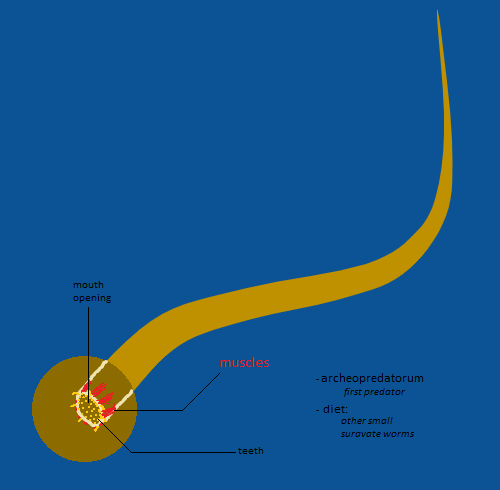

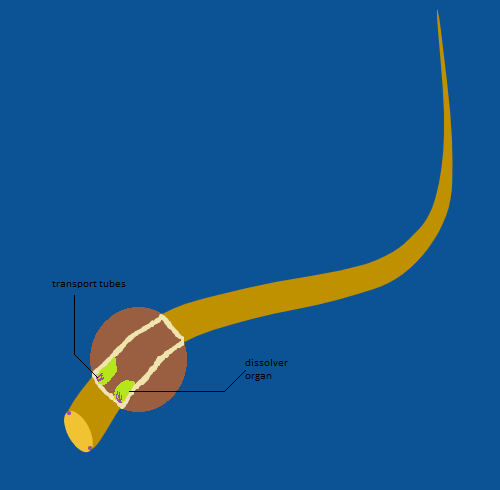

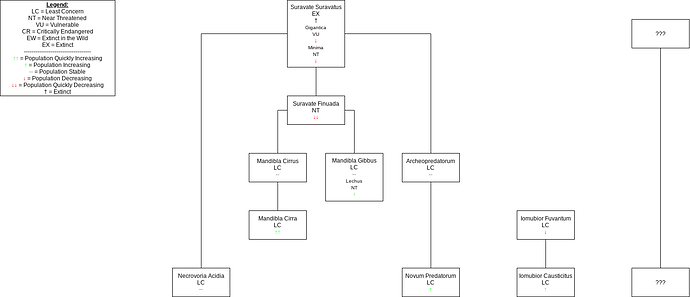

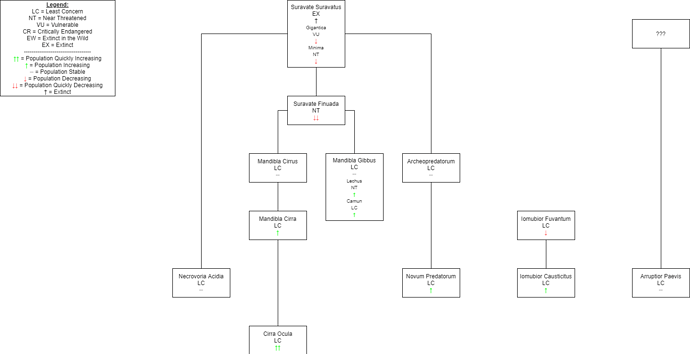

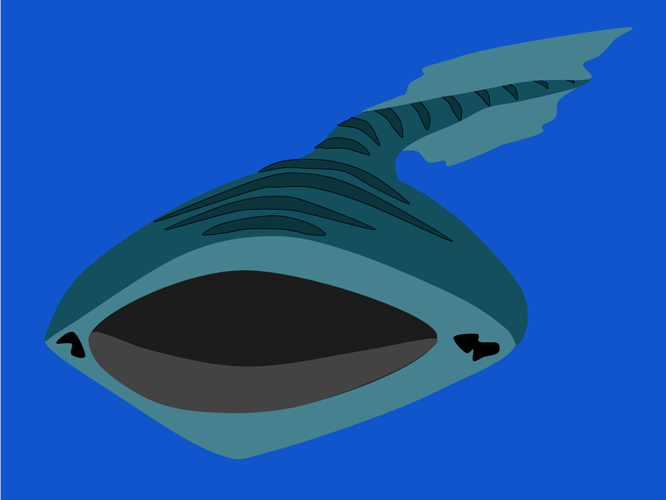

Meet Suravate Suravatus. This is a multicellular worm-thing, which flits around in the water, using it’s porous (more of a flat surface than a mouth really) to absorb nutrients. This worm is pretty efficient at using it’s energy, and it has proliferated because of a recent nutrient boom underwater. It reproduces by having a gamete bud off the tail, and mix in the water with some other haploid, causing a new worm to be made sexually. It is an invertebrate, and it has a few nerves but nothing too big. The biggest one has been seen at about 3 cm, and on average they are 0.75 to 1.25 mm. (Forgot to include scale, my b)

Now, let’s begin the game. Since so many Suravatus are appearing, there are bound to be mutations. So, here’s the system I came up with. It’s very similar to Noinova, if any of you have played that forum game. All credit goes to Spleehae. I recommend it, but I’m going off on a tangent. Nobody owns a species, and at any time, you may cause one mutation to a species. You can do multiple species in one post, but if you make a new species in one post, you cannot improve on it in the same post. I will be deciding what lives and what dies, although that’s mostly going to depend on the nature of mutations. Random events may occur, and because of these, entire species may be made or go extinct. The battle for worldwide supremacy is on! Oh yeah, also, you need to make pictures for the species or mutations that occur. If you need any help with that, just describe the mutation to me and I will make it.

I would advise following the template below, but you don’t have to. Just make sure you have all of the parts.

New Species (If it’s not too big of a mutation just keep the species the same):

Old Species:

Mutation and Description:

[Insert the picture here]